Watercourses on Romney Marsh

The flatness of Romney Marsh, with many areas lying below sea level, requires a complicated drainage system to ensure that flooding does not occur. Most of the reclaimed land is bounded by dykes or larger watercourses known as sewers.

Watercourses on Romney Marsh include every river, stream, ditch, drain, cut, dyke, sluice, sewer (other than a public sewer) and passage through which water flows and which does not form part of a main river. They drain through sluices and outfalls into the sea and through pumping stations into the Royal Military Canal.

The watercoures form a dense network of drainage ditches which are essential to the continued survival of the Marsh, given such a large proportion of it is below sea level.

Most of the larger drainage sewers on the Marsh are of considerable age, some following the course of past creeks on the ancient salt marshes and some being mentioned in charters of the 13th century.

Smaller channels, about 6-8ft wide at bank level and known as dykes, form a network of minor drainage channels connecting the main sewers of the Marsh.

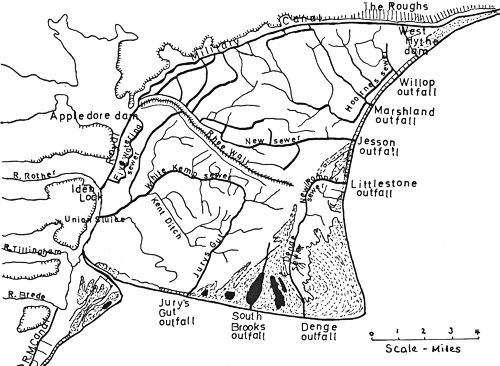

Main Sewers and Outfalls on Romney Marsh

Map Showing the Large Number of Watercourses on Romney Marsh

The drainage sewers, dykes and ditches, know locally drain the water from the farm land and allow it to flow either to the sea via outfalls or is pumped in to the Royal Military Canal, eventually also ending up in the sea. Some of the ditches are narrow and less than one metre deep. These usually dry up in the Summer. Wider sections are like a bright green carpet where you can sail a small dinghy.

The sewers, dykes and ditches provide a home for fish, water flies, water snails and all kinds of weeds. Fishing is enjoyed from the banks for roach and tiddlers like stickleback and minnows. Eels can be caught by pulling in weeds. Areas of the banks are scattered with wildflowers, shaded by hawthorn and elderberry bushes.

The extensive systems of ditches and dykes are important examples of lowland, slow-moving and eutrophic (nutrient-rich) waters. There is a brackish influence near the sea and also inland in the large ditches or where peat deposits, which leach salt, lie close to the surface. The majority of the ditches have high plant species richness. Because of this, many have been designated Sites of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI). ![]() Find out more.

Find out more.

Typical Watercoure on Romney Marsh

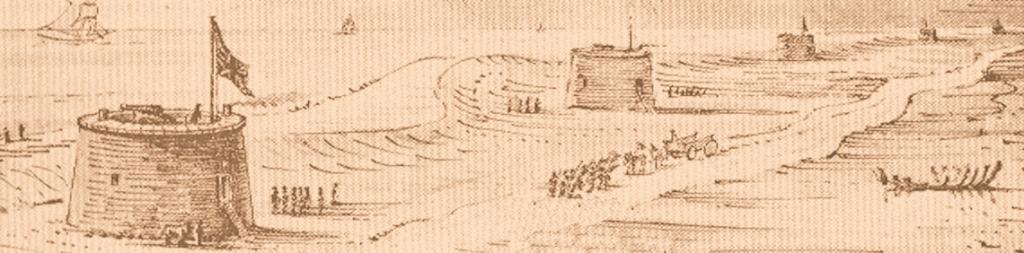

History

Land drainage has been important to Romney Marsh for hundreds of years. In 1252 the future Henry III granted a charter known as the Charter of Romney Marsh to protect the Jurats of Romney Marsh against interference from the Sheriff or his officers in making proper provision for the defence of the Marsh against the flooding of the sea and flooding of freshwater. This Charter was confirmed by other Royal monarchs and by the end of the Middle Ages there was what was known as the “Laws and Constitutions of Romney Marsh”. When Parliament introduced statutory regulation in 1531 with Commissions of Sewers, Romney Marsh was exempted because the system worked so well.

From 1252 until 1932, the Bailiff, Jurats and Commonalty of the Marsh of Romney levied Scots, or rates, on the occupants of the Marsh for the maintenance of the sea defences and land drainage system.

Outfall into the sea at Greatstone

In 1462 Edward VI granted a Charter which gave the Corporation of Romney Marsh the power to raise taxes in addition to the scots levied in respect of sea defences and land drainage. The Charter allowed the formation of the body known as The Lords, Bailiff, Jurats and Commonalty of the Level and Liberty of Romney Marsh, the Level being the drainage district.

Following the Land Drainage Act of 1930, responsibilities for sea defence and land drainage were split into Catchment Boards and Internal Drainage Boards. Originally six Boards operated in the area but two amalgamated leaving five Boards: The Romney Marsh Levels, Walland, Denge and Southbrooks, Rother and Pett.

In 1932 the responsibility passed to the Romney and Denge Marsh Main Drains Catchment Board; in 1937 to the Kent Rivers Catchment Board; in 1950 to the Kent River Board and in 1965 to the Kent River Authority, who, with the Romney Marsh Level Internal Drainage Board as the land drainage rating authority, are currently responsible for the well-being of an area of land almost entirely below high tide level.

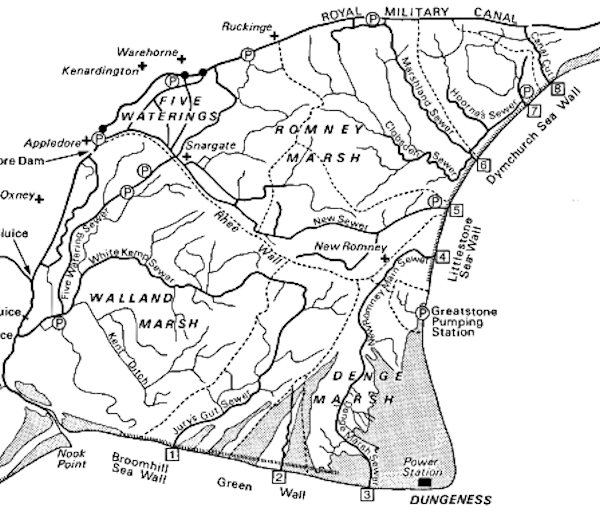

Romney Marsh Area Internal Drainage Board

About 220 miles of these watercourses are now maintained and managed for sustainable water levels by the Romney Marsh Area Internal Drainage Board. The rest are the responsibility of the Environment Agency.

It is essential for the drainage of the Marsh that the watercourses are kept clear to allow the free flow of water. The water drains either into the Royal Military Canal via pumping stations or the sea via sluices/outfalls.

The Drainage Board and the Environment Agency work together to run a comprehensive reed cutting program to allow water to flow with maximum efficiency off of the marsh. This is mainly carried out using mechanical weed cutters; however, in some instances where access is difficult for machinery, this is done by hand. Three years ago they also began a de-silting program to maintain current river capability.

Pumping Station next to the Royal Military Canal

Map showing sewers, outfalls and pumping stations

Mole Drainage

In addition to the watercourses, many of the farms on Romney Marsh have to use further land drainage methods to ensure their land is suitable for crop growing.

The most common method used on the Marsh is mole drainage. Mole drainage is produced by drawing a mole plough, which is a bullet-shaped instrument usually less than 20 cm in diameter, through the soil to produce a continuous passage. Mole drains are established at a depth of about 40-60 cm, with a lateral spacing of about 2-5m. They are not permanent features and are susceptible to collapse and sediment blockage. Consequently, they have to be renewed on a regular basis, usually after a period of about 5-7 years. During the installation of mole drainage, the moisture status of the soil is of crucial importance. If conditions are too wet, smearing and consolidation may result, while shattering may occur if the soil is too dry. In spite of the temporary nature of mole drainage, it is often adopted in preference to other drainage practices because it is cheap and easy to install. It is also commonly used as a form of secondary drainage in combination with primary tile or ditch drains