Black Death

The Black Death is the name given to a deadly plague which had a major effect on sheep farming on Romney Marsh. The Black Death was one of the worst catastrophes in recorded history – a deadly bubonic plague that ravaged communities across Europe, changing forever their social and economic fabric.

The Black Death was one of the most devastating pandemics in human history, resulting in the deaths of an estimated 75 to 200 million people and peaking in Europe in the years 1346–53.

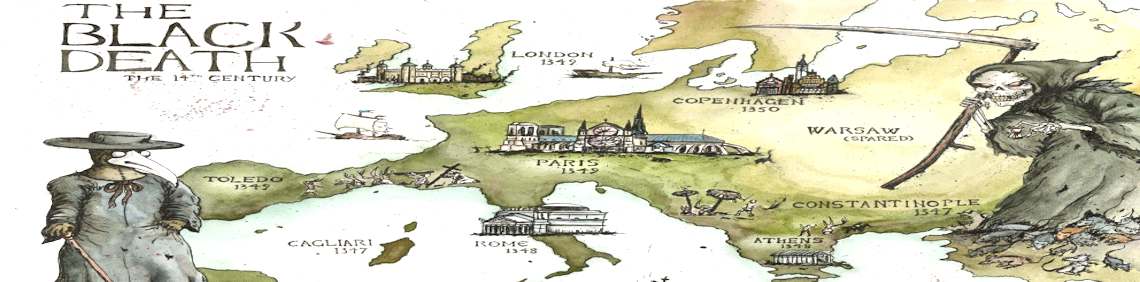

In the early 1330s an outbreak of deadly bubonic plague occurred in China. The bubonic plague mainly affects rodents, but fleas can transmit the disease to people. Once people are infected, they infect others very rapidly.

Plague causes fever and a painful swelling of the lymph glands called buboes, which is how it gets its name. The disease also causes spots on the skin that are red at first and then turn black. The disease struck and killed people with terrible speed.

It has long been thought that the plague, caused by the bacterium Yersinia pestis, which lasted in Europe until the early 19th century, was spread by rats. The rodents and their fleas were thought to have spread a series of outbreaks in 14th-19th Century Europe.

But accoring to a study in 2018, rats were not to blame for the spread of plague during

the Black Death.

![]() History Extra Podcast The Black Death

History Extra Podcast The Black Death

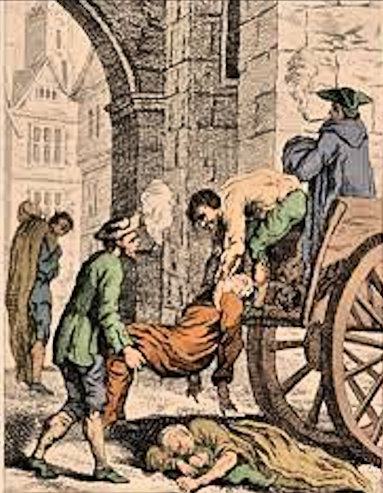

Clearing the dead

Scientists from the University of Oslo and the University of Ferrara believe human "ectoparasites", such as body lice and human fleas, might be more likely to have caused the epidemic. The study, in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Science, uses records of its pattern and scale.

Since China was one of the busiest of the world's trading nations, it was only a matter of time before the outbreak of plague in China spread to western Asia and Europe.

Spreading throughout the Mediterranean and Europe, the Black Death is estimated to have killed 30–60% of Europe's total population. In total, the plague reduced the world population from an estimated 450 million down to 350–375 million in the 14th century. The world population as a whole did not recover to pre-plague levels until the 17th century.

The plague recurred occasionally in Europe until the 19th century.

The Black Death arrived in Wemouth in Britain from central Asia in the autumn of 1348, and by late spring the following year it had killed six out of every 10 people in London. On Romney Marsh, the already low population, fell by over half with mortality rates on the Marsh being twice as high as in villages just a few miles away.

Romney Marsh

On the Romney Marsh, the Black Death was thought to have been bought to the area by smugglers who were exporting wool across to France where the disease was rife, so as well as bringing back to England their contraband they also bought back the Black Death.

Communities on the Romney Marsh were seriously affected and many of these were simply swept away and never to appear again, only the ruins of the churches remain and all signs of the early life totally gone.

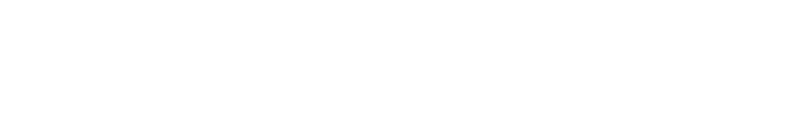

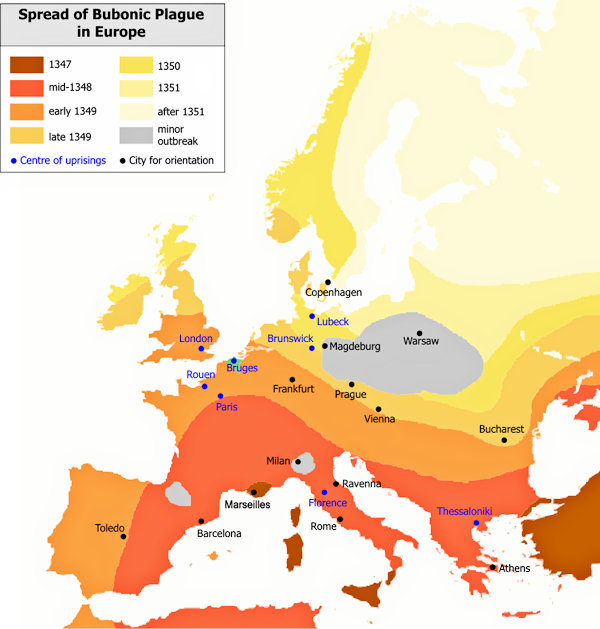

Map of Spread of the Black Death

Some of these are the villages of Blackmanstone, Broomhill, Eastbridge, and Midley (see Lost Villages). When one walks around what is left of these ruins there is such an eerie feeling, no signs of any graves or the homes they would have lived in, and if only the walls could talk they would probably tell us about the sheer terror of what happened during that terrible period.

The viilage of Hope was also seriously affected and by 1589 there were only four dwelling-houses in the parish.

This reduction in the population of the Marsh meant that there were not enough people to culitvate the land to grow crops and/or dairy farm. This resulted in a significant change from arable etc farming to sheep farming with the Marsh being divided into large sheep grazed pastures more easily looked after by fewer people - and the Romney Marsh sheep industry was born.

some text courtesy of Colin Walker of the DDHG

![]() Find out more - Article by Mark Ormrod Professor of History at the University of York

Find out more - Article by Mark Ormrod Professor of History at the University of York

The Black Death devasted 14th century Britain

William de la Dene, a public notary between 1317 and 1354, wrote in his Historia Roffensis (History of Rochester):

"A great mortality ... destroyed more than a third of the men, women and children. As a result, there was such a shortage of servants, craftsmen, and workmen, and of agricultural workers and labourers, that a great many lords and people, although well-endowed with goods and possessions, were yet without service and attendance. Alas, this mortality devoured such a multitude of both sexes that no one could be found to carry the bodies of the dead to burial, but men and women carried the bodies of their own little ones to church on their shoulders and threw them into mass graves, from which arose such a stink that it was barely possible for anyone to go past a churchyard. As remarked above, such a shortage of workers ensued that the humble turned up their noses at employment, and could scarcely be persuaded to serve the eminent unless for triple wages. Instead, because of the doles handed out at funerals, those who once had to work now began to have time for idleness, thieving and other outrages, and thus the poor and servile have been enriched and the rich impoverished. As a result, churchmen, knights and other worthies have been forced to thresh their corn, plough the land and perform every other unskilled task if they are to make their own bread."