New Romney Historical Information

Extract from Kent Historic Towns Survey of NEW ROMNEY

Archaeological Assessment Document

published by Kent Count Council December 2004 ![]() Read Full Document

Read Full Document

4. HISTORICAL DATA BY PERIOD

4.1 Pre-urban evidence

4.1.1 Prehistoric period

The shingle spur on which New Romney was founded probably began to form during the late neolithic period. Between c. 5000 BC and AD 500 a long shingle spit, probably caused by easterly longshore drift, was deposited between Hastings and Hythe, resulting in a barrier behind which a salt marsh developed through silting by waterways from the Weald. The waterways finally merged to form the river Limen (later called the Rother). Sometime c. AD 450-700 the shingle barrier was breached by the sea, creating a wide marine inlet and an outlet for the river Limen between Dymchurch and Lydd. By the mid-eighth century a shingle spur on the north-eastern side of this new inlet was occupied by a small settlement consisting of fishermen’s huts and an early church, that of St Martin.

4.2 Urban evidence

4.2.1 The Saxon period

The traditional view that New Romney was a resettlement of the earlier town of Old Romney is now disputed. Recent fieldwork and documentary study suggest that Old Romney was not the predecessor of New Romney, but a scattered village with a concentration around the 6 surviving church of St Clement, and that the Romenel of Domesday Book was situated close to the Saxon church of St Martin.

It is uncertain when settlement began at New Romney; the oratory and fishermen’s houses may be referred to in the charter of AD 741 (see above). The oratory has been identified with the church of St Martin, New Romney, by the mouth of the river Limen. The settlement must then have grown in size and importance, and it may have been threatened by the Danes when, in AD 893, a fleet of 250 ships entered the estuary of the Limen and sailed up to Appledore.

By the tenth century New Romney and much of the surrounding land had passed out of the hands of the nunnery at Lyminge to the archbishop. A mint was established during the reign of Aethelred II (c. 997-1003) and a port was founded there, probably by the archbishop, c. 1000. By the reign of Edward the Confessor the town and port had become well established and was supplying the King with ship service as one of the original Cinque Ports.

4.2.2.The medieval period

In 1066 the men of New Romney repulsed William, Duke of Normandy when he and some of his soldiers attempted to land there. The invading force then went on to land at Pevensey in Sussex. As a consequence, after the Battle of Hastings, the town and port of New Romney was one of the first places to be subdued by William. Twenty years later New Romney had a population of 650 to 800, a harbour, a church and a mint. The town was laid out in a grid pattern, with twelve or more blocks of properties stretching along an east-west axis, with marshland to the north, the river Limen to the west and north-west, and the sea to the east and south-east (Figures 4 and 5).

4.2.2.1 Markets and fairs

New Romney probably had a market by the late tenth or early eleventh century, and almost certainly before AD 1200 when it is likely to have been one of the privileges of a Cinque port. The early market may have been by the harbour, but later it was probably held in the middle of the High Street where the road widens and where a market cross once stood. This was a common arrangement in undefended market towns. The market (for poultry, fish, livestock and general goods) was held weekly on a Saturday. The poultry and perhaps butchers’ markets may have occupied a small triangular area of open land at the junction of Church Road with Rome Road and Lion’s Road (formerly West Street), next to St Lawrence’s church, for in the late fourteenth century it is called ‘the Poultry’ and in 1414 two stalls in the butcher’s market are mentioned in the same place. The site may also have been used for the annual St Lawrence Fair, held on 19th August and the days before and after.

4.2.2.2 The manor

After 1066, the archbishop of Canterbury, who provided a bailiff for the town, held the manor. As New Romney was a Cinque port the townsfolk enjoyed a state of virtual autonomy and the barons and jurats (the ruling body of the town) frequently disputed the archbishops’ alleged encroachments on New Romney’s privileges. By the end of the fourteenth century the influence of the church had diminished and the town was generally successful.

4.2.2.3 The churches

New Romney was within the ecclesiastical jurisdiction of the diocese of Canterbury and the deanery of Lympne. The town was divided into twelve wards spread among three parishes 7 each with its own church, St Nicholas, St Martin and St Lawrence. By 1282 St Nicholas had become the prime church and St Martin and St Lawrence dependent chapels.

The church of St Martin

St Martin’s was the first church recorded at Romney, probably being the oratorium of St Martin mentioned in AD 741. No details of this church are known, but it was probably built of wood. It was later rebuilt in stone, perhaps in the tenth or early eleventh century when the town of New Romney seems to have been laid out.

The church of St Martin, mentioned in the Domesday Monachorum of c.1089 as subordinate to the minster church at Lympne, stood on the green at the corner of Ashford Road and Fairfield Road, a little north of St Nicholas church to which it was subservient by the mid thirteenth century. In 1511 Archbishop Warham reported that the chancel, not having been repaired, was so decayed that it might fall down, and by 1549 the whole church was in a state of decay. Eventually, the municipal authorities petitioned the archbishop to allow either St Martin’s or St Nicholas’s to be demolished because the town was too small to support both. St Martin’s was demolished in 1549 and its materials and plate were sold.

Very little is known of its structure, but the first stone church may have had a late Saxon cruciform plan. That church was replaced or enlarged in the twelfth or thirteenth century, after which it may have consisted of a chancel, nave, tower, transepts, side chancels, aisles, a vestry and a porch. The tower contained a peal of five bells, transferred to St Nicholas church when St Martin’s was demolished. After the demolition, the site of the church and its surrounding churchyard became part of the glebe of vicar of St Nicholas’s, and is now an open space.

The church of St Lawrence

The church of St Lawrence stood on a small site, with no room for a churchyard, between the High Street and Church Road. The date of its foundation is not known but it is listed in the Domesday Monachorum of c. 1089, where it is shown as being subordinate to the minster church of Lympne. By the thirteenth century, it had become subservient to St Nicholas, New Romney. From 1477 to 1500 the jurats attended the church on the feast of the Annunciation of the Virgin to elect their bailiff. By 1511 the chancel was in need of repair, but nothing was done and the church was demolished sometime before 1539, and its building materials sold.

Nothing is known of the plan of the church, but documentary references indicate that it had a chancel, a nave, a high tower containing the town clock, and at least four altars, dedicated to St Katherine, The Holy Trinity, St John the Baptist and St Thomas of Dancastre. It appears to have been built of courses of flint and stone with a tiled floor. As it had no burial ground; some parishioners were buried within the church itself and others were interred in the cemetery of the hospital of St John the Baptist.

The church of St Nicholas

St Nicholas, dedicated to the patron saint of mariners, is listed in the Domesday Monachorum of c. 1089, but the present church was built c. 1160-1170. In 1264 St Nicholas became a cell of the abbey of Pontigny in France, and it remained so until the suppression of the alien houses in 1414, when it passed to the Crown. In 1438 Henry VI gave it to the College of All Souls, Oxford. 8 In 1282 it had become the parish church of New Romney with the churches of St Martin and St Lawrence demoted to dependent chapels. In the Taxatio of Pope Nicholas IV of 1291 it was valued at £20. For most of the Middle Ages, the church was used for town functions, particularly the regular sessions of the jurats and annual Cinque port meetings).

The lowest three stages of the great west tower and most of the nave and aisle date from c. 1160-1170. The two upper stages of the tower with four unequal stone pinnacles and a central octagonal stone structure, probably the base for a spire, were added c.1200. The tower was then c. 9m square and c. 30m high, with a peal of eight bells. In the early fourteenth century the church was extended by the addition of a bay at the eastern end in the nave and a new chancel with side aisle. The great storm and flood of 1287, which deposited up to 1m of sand and shingle across the area and damaged or destroyed much of the medieval town, raised the ground level so much that the new aisles and chancel were built at a higher level than the nave.

4.2.2.4 Other religious organisations

The hospital of SS Stephen and Thomas

The hospital of SS Stephen and Thomas was situated beyond the western limits of the town near present day Spitalfield Road and Priory Close. Adam de Cherryng founded it as a leper hospital between 1184 and 1190; Robert, a leper, was recorded as one of the inmates in 1255. Although provision for thirteen or fifteen men and women was proposed in 1322, the hospital was empty and almost derelict by the middle of the fourteenth century. In 1363 it was refounded to include a chantry chapel with two priests, one of whom should be the resident master or warden, and accommodation for the poor of the town.

It was dissolved in 1481, when it was ruinous, and annexed to Magdalene College, Oxford, which still possesses a map from 1614 showing the hospital standing on the west side of New Romney. Excavations near Spitalfield Road in 1935 revealed fragmentary foundations and other remains of the hospital’s c. 1363 chapel, and a skeleton was discovered during building works in Priory Close in 1955. Further excavations in 1959 uncovered two thirteenth century or earlier structures, one of which is thought to have been the chapel; the other may have been possibly a hall for the master and clerks. Burials were also found adjacent to the chapel, but there was no trace of the wooden cells customarily used for housing lepers.

The hospital of St John the Baptist

The medieval hospital of St John the Baptist stood on a large site at the west end of the town. Nothing is known about the foundation of the house, which was under the authority of the town jurats. It appears to have been a hospital for both sexes, under the governance of two or three officers, one of whom was referred to as the master or prior, and another as seneschal or steward. The earliest recorded reference to the hospital dates from 1399. In 1401 the house is recorded as lending £10 to the Corporation; this was repaid in 1408. Another mention in 1434 concerns the leasing out of the land in Lydd. From 1495 onwards the Corporation received rent for ‘the house of St John the Baptist’, so by then the foundation had probably ceased to be a hospital.

In 1929 foundations, bones and skeletons were found on the north side of St John’s Road and further burials were found near St John’s Road and Sussex Road during the late 1970s and in 1995 during construction work. 9 The Franciscan friary A house of Franciscan friars was founded in New Romney sometime before 1241, and there were fourteen friars in 1243. It was no longer in existence by c.1287, perhaps being abandoned following the great storm of that year.

The Cistercian priory

A Cistercian priory may have stood on the west side of present day Ashford Road. In 1222 Archbishop Langton granted 50 marks annually from the church of Romney to the Cistercian abbey of Pontigny, France, and in 1238 the grant was raised to 60 marks. It is doubtful, however, whether there was ever a regular settlement of monks in New Romney, and the building behind the modern St John’s Priory House in the High Street may be the remains of a grange belonging to Pontigny, rather than a priory. When the possessions of the alien houses were confiscated in 1414, Romney was acquired by the Crown and given to the warden and college of All Souls, Oxford in 1439.

4.2.2.5 Industry and trade

Although medieval coins minted in New Romney and found in continental ports indicate early trading links with Europe, the earliest surviving record of New Romney’s trade is Daniel Rough’s Memoranda Book (begun 1352), which contains a list of dues levied on tradesmen and market transactions. Seafaring activities are suggested by the presence of a ‘master carpenter of ships’ (a designation supported by the clench nails found in 2001 on the Southlands School site) and ‘master fishermen’ and by the produce sold in the market, such as coal and fish. Fourteenth-century trading licences illustrate the imports into and exports from New Romney; for example, corn, cheese, butter, beans and oats were sent to Flanders and Gascony, and wine was imported in return. Tradesmen such as barbers, carpenters, cobblers, fishermen, goldsmiths, merchants and vintners are listed in the Poll Tax of 1380, which also mentions a town mill and three other windmills. Romney Warren, a common over 400 acres in extent on the east side of town, was used for breeding rabbits for food and a keeper was employed to guard the Corporation’s rabbits.

The Cinque ports connection

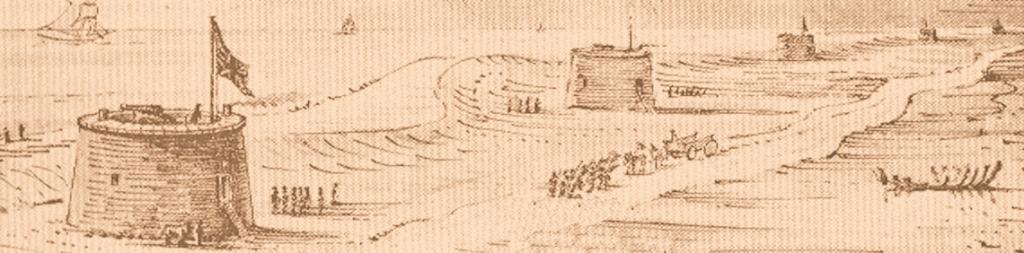

The Confederation of the Cinque Ports was a group of five towns (Hastings, Romney, Hythe, Dover and Sandwich) which were deemed capable of providing the king with ships and men to protect the coastal waters around south-east England and to transport soldiers to the Continent (ship service). It was active from the eleventh century until the sixteenth century. All the towns had harbours and fishing fleets, and in return for their ship service, they received a degree of autonomy and urban privileges.

After the Norman Conquest, William I appears to have continued the ship-service arrangements that had evolved during Edward the Confessor’s reign.

In 1111 Henry II granted charters to the original Cinque Ports and the two ‘Antient Ports’ of Winchelsea and Rye, giving them rights and privileges in return for supplying up to 57 fully-manned ships for the king’s use. Lydd was made a corporate member (limb) of New Romney in 1155; it also had four non-corporate members, including Old Romney. Edward I’s Great Charter of 1278, demanded that New Romney and Old Romney should provide four ships and Lydd one ship, and in 1364 Edward III confirmed the details and privileges of the 1111 charter.

The Cinque Ports Confederation saw much action during the thirteenth-century wars with France and against rising levels of piracy. The great storm of 1287, however, virtually 10 destroyed the town of New Romney and blocked its harbour, so that by 1351 it was unable to find its quota for ship service, and for a while lost its privileges as a Cinque Port.

The port and the storm of 1287

The site of Romney’s medieval harbour has not yet been identified but it probably lay to the south of St Nicholas church, where the slope in the ground level may reflect the old shoreline (Figures 4 and 5). The harbour was no longer viable c. 1540 although ships had anchored ‘in [St Nicholas] churchyard’ within living memory. In c. 1950, a workman digging new foundations for a bridge to carry Church Lane across the Main Sewer discovered the remains of timber beams of a wharf, which had once stood near St Nicholas’s churchyard. In 2001 excavations on the site of Southlands School in Fairfield Road provided more information about the position of the harbour. The earliest archaeological remains were foreshore deposits sealed by a layer of sand dated after 1250, above which there was a level indicating domestic occupation and finally a waterfront structure with associated industrial activity. The discovery of clench nails indicates that shipbuilding or ship repairing took place there.

By the twelfth century, the course of the river Limen (or the Newenden river as it was also called) had begun to silt up, and when, in the early twelfth century, the shingle bank near Winchelsea was breached, that gap became the river’s outlet to the sea. New Romney thus lost its riverine connection with the Weald. In response to this, a canal (the Rhee Channel) was dug to connect New Romney with the river Limen south of Appledore. Its exact date of construction is unknown, but in the 1250s it became blocked and documents of the mid-thirteenth century mention attempts to remedy the situation by constructing sluices to encourage a greater flow of water downstream to New Romney.

The thirteenth century was also a period of great storms, particularly severe ones occurring in 1250, 1252 and 1287.

The Southlands School excavations revealed several layers of flood-deposited sand, one of which may have derived from the flood of 1252. A second similar deposit lay above the waterfront mentioned above and may represent the flood of 1287. The 1287 storm was devastating for New Romney; it breached most of the sea defences, partially destroyed areas of the town, deposited large quantities of sand and shingle c. 1m deep across a large part of the settlement, and completely blocked the end of the Rhee Channel and the harbour. After the storms, the sea defences were repaired and the Rhee Channel opened up again, but serious silting occurred during the second half of the fourteenth century and there are numerous records of attempted clearance in the 1380s, 1406, 1409 and 1413. Despite this, the Rhee Channel dried up. By 1427 it was let out for pasture and by 1545 dwellings were even being erected along its course.

The sea also retreated from New Romney, and in the reign of Henry VIII it was c. 1.5 km from the town. This was the end of New Romney as a port (Figures 6 and 7). The mint ‘Long Cross’ pennies (c. 997-1003), ‘Helmet’ pennies (1003-1009) and ‘Small Cross’ pennies (1009-1017) attest the continuous presence of a mint in New Romney from the end of the tenth century until 1067. It resumed in 1077 and continued until 1100. After another break, the mint struck coins intermittently until 1134, when it ceased permanently. Fishing formed a major part of the local economy, with at least eight fishing vessels mentioned in the fourteenth century. Herrings, sprats, turbots, mullet and even porpoises were 11 caught, and the catches must have been quite high, for in 1413 John Payne was prosecuted for profiteering from the sale of 7,000 herrings. Once the harbour fell out of use the fishing boats were beached on the Warren Salts, east of the town. Inns By the early fourteenth century New Romney had some taverns, although none survives. In 1427 two ‘ale conners’ were appointed to strain and taste the beer manufactured in the town.

4.2.3 The post-medieval period

By the beginning of the post-medieval period New Romney, although still a member of the Cinque Ports Confederation, had neither port nor coast (Figure 6) and its economy had become dependent on agriculture rather than fishing and international maritime trade. It could no longer provide ship service for its Cinque Port obligations, its market had declined, its population had dwindled, and its three parish churches had been reduced to one.

4.2.3.1 Markets and fairs

The weekly Saturday market continued to be held in the High Street but on a much smaller scale than before, and the fair also persisted until the nineteenth century when both were discontinued. In 1702 a town hall was built on the southeast side of the High Street, with an open arcade at ground level to accommodate market stalls, but by the late nineteenth century, the arcade had been filled in and turned into offices.

4.2.3.2 The church of St Nicholas

In 1588 the church was valued at £90 and had 351 communicants. By 1640 its value had increased to £105, with the same number of communicants. The jurats and, after 1575, the mayor and council continued to hold their meetings in the church, and All Souls’ College kept the advowson. Restoration of the church began in 1880, but as this would have entailed demolishing some of twelfth century north aisle there was a local outcry and protests from the newly formed Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings. The work was stopped and no thoroughgoing restoration has since been undertaken, although there has been piecemeal work since the storms of the 1980s.

4.2.3.3 Southland’s hospital

In 1610, John Southland, a town magistrate from a wealthy New Romney family, bequeathed property in the town and elsewhere in Kent to found and maintain a hospital or almshouse for the poor. Four houses in West Street were named after the founder. In 1728 they were further endowed, and in 1734 were rebuilt as two-storey brick structures. The houses survive as Southland’s Almshouses. Southland also provided for a schoolmaster to administer the hospital’s property and ‘from time to time to teach two poor children to read and write English and Latin and to learn arithmetic until they were fourteen years of age’. The modern school commemorates this in its name.

4.2.3.4 The charter of incorporation and the town council

When the town acquired its Charter of Incorporation in 1562, a mayor and council of five jurats and 26 free men replaced the archbishop’s bailiff. The mayor was to be elected 12 annually in the parish church. Election in the church continued until 1835 although a town hall for the council’s administrative functions was built in the High Street in 1702. The Local Government Act of 1972 caused New Romney to be absorbed into the new Shepway District Council.

4.2.3.5 Industry and trade

By the seventeenth century, New Romney’s economy was based mainly on mixed farming, with a little fishing. Craftsmen and tradesmen such as carpenters, blacksmiths, cobblers, millers, weavers and shopkeepers helped to keep the town largely self-supporting, and there were many farms providing employment in the area.

The Cinque Ports connection

When New Romney and Lydd were required to provide a ship of 50 tons to join the fleet against the Spanish Armada in 1588, they had to hire the John of Chichester at a cost of £300. This was the last offensive operation carried out by the Cinque Ports Confederation, although the Confederation is still maintained, and New Romney is still a member.

Agriculture

Considerable areas of salt marsh were drained to provide grazing, and by the seventeenth century, Romney Marsh was the chief sheep-grazing area of the country. Between 1600 and 1620 the average flock was more than treble the size of those in other regions, and by 1700 they were more than five times larger than flocks elsewhere. Cattle were also reared. Most of the sheep and cattle were driven to local and London markets, and ‘Kentish wool’ was also in great demand. This type of farming continued to flourish throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries; even today sheep are bred and cattle raised on small farms, particularly around New Romney, although arable farming on a larger scale is becoming more common.

Mills

There were at least five windmills in the vicinity of New and Old Romney in the fourteenth century, one of them (Town Mill or High Mill) being reported as in a dilapidated condition c. 1500. It must have been rebuilt, however, for it appears on maps of 1596, 1769, 1799 and 1898. It was rebuilt again in 1794 and was still working in 1894 but it was demolished during World War I because it was a potential landmark if the enemy invaded. The other mills shown on the maps (Figures 7 to 13) have all been demolished without record.

Inns

In 1686 New Romney had inns with a total of 19 guest beds and stabling for 41 horses. Some of the inns may have been medieval in origin. For example, The New Inn in the High Street is a possibly fourteenth-century timber-framed structure with an eighteenth-century façade. Others, including The Dolphin and The Rose and Crown, both in the High Street, seem to have been founded in the seventeenth century or even earlier. The Dolphin Inn is first recorded in 1735 with stables being mentioned in 1746. The Rose and Crown is first mentioned in 1742, and in 1743 its stables were said to be full of smugglers’ horses. The Cinque Port Arms at the west end and the Ship Hotel at the east end of the High Street were inns in the eighteenth century, although both occupy medieval buildings. The Plough Inn east of the town is dated 1776, whilst the Prince of Wales, once in Fairfield Road, was of early nineteenth century date.

Coaching services

New Romney was not on a main coaching route but some coaches between Hythe and Hastings passed through the town during the early nineteenth century. The road from New Romney to Lydd was turnpiked between 1750 and 1780 but was little used because the inhabitants on Romney Marsh were so sparse and poor.

4.2.3.6 The railway In 1851

The South Eastern Railway Company opened a line between Ashford and Hastings with a station at Appledore about 9km west of New Romney. A branch line from Appledore to Lydd was built in 1881-82, and the line was extended to New Romney in 1884 when a station and The Railway Hotel were built. The line was closed to passenger traffic in March 1967, and the track was dismantled. Today, the only rail connection to New Romney is the narrow gauge Romney, Hythe and Dymchurch Light Railway, built 1927 - 1929.

4.2.4 The modern town

New Romney today is relatively small, more a large village than a town, not having experienced the growth of some other small market towns such as Ashford, Sevenoaks and Tonbridge. The High Street is the commercial centre, with shops, banks, pubs and other local services, and also a number of historic buildings, mostly dating from the seventeenth century and later although some are earlier.

The core of the town changed somewhat during the nineteenth and early twentieth century when many old buildings were replaced and some gaps infilled. Nineteenth century building also took place to the west of the town and there was ribbon development along Fairfield Road to the east. The twentieth century saw rebuildings and replacements in the High Street and the construction of several large housing estates to the west, the southeast and the northeast. The Warren site east of St Mary’s Road is now occupied by new housing. Nevertheless, the early grid plan of the town has been preserved relatively intact (Figures 9 to 13).

There is no large-scale industry in New Romney and local employment is mainly confined to small service industries, supplemented by Lydd Airport, Lydd Camp, Dungeness Power Station and various gravel quarries. Commuting to other employment centres such as Ashford and Folkestone is becoming more common although there is no longer a mainline railway in the town. A few people work on the farms in the neighbourhood.

4.2.5 Population

There were probably 625-800 inhabitants in New Romney in 1086. This figure may have increased during the twelfth and thirteenth century as the port flourished, but the severe storms of the second half of the thirteenth century had dramatic effects on the population as many people who depended on the river and the sea lost their livelihoods. By the late sixteenth century Romney Marsh was one the most sparsely populated areas of Kent, reputedly as it was ‘Evill in Winter, grievous in Sommer, and never good’.

In 1588 New Romney probably had c. 450 inhabitants and there were 412 in 1676. The first official census in 1801 listed 755 people; this number rose to 983 in 1831 and 1,053 in 1851 but stagnated for the next 30 years, reaching only 1,026 in 1881.

Between 1881 and 1921 there was a gradual rise in the population, to 1,659. Growth continued to be slow until 1966 when there were c. 2,600 people in New Romney, but since then new housing estates in New 14 Romney and neighbouring Greatstone and Littlestone (within the present parish of New Romney) had encouraged the population to rise to 6,208 in 1991

You can read the complete document at https://archaeologydataservice.ac.uk/archiveDS/archiveDownload?t=arch-459-1/dissemination/pdf/New_Romney.pdf