Wars with France 1793 to 1815

use keyboard shortcut Ctrl+F

[Command+F on a Mac] and enter the subject/word you wish to find.

The banner image at the top of this page is "Scotland Forever!", an 1881 painting by Lady Butler depicting the start of the cavalry charge of the Royal Scots Greys who charged alongside the British heavy cavalry at the Battle of Waterloo in 1815 which ended the Napoleonic wars.

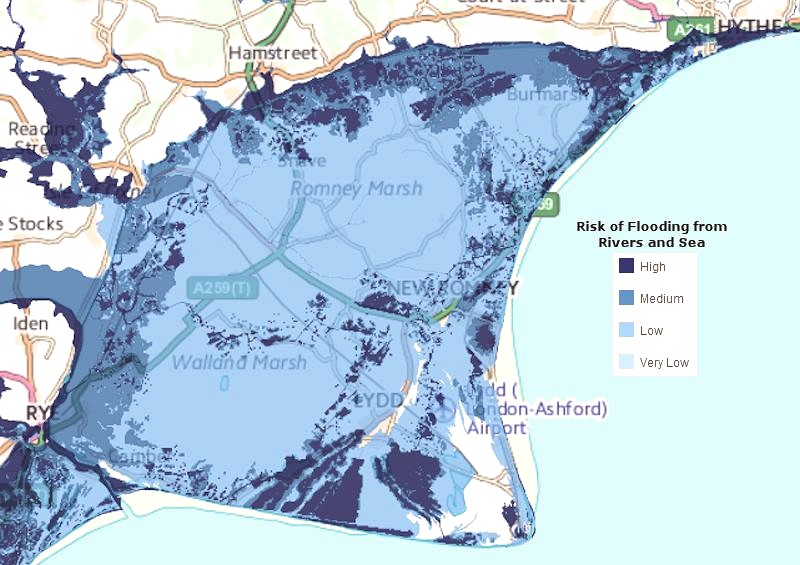

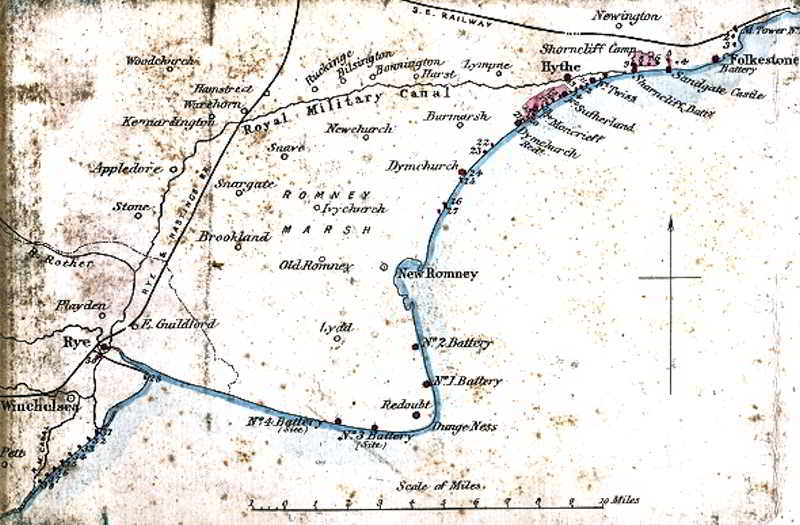

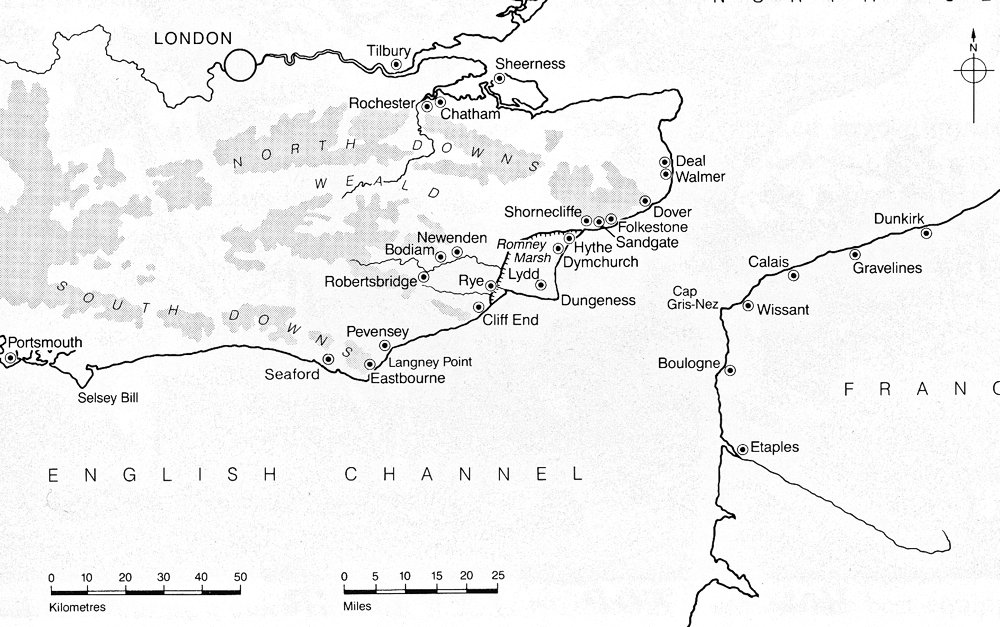

1867 Map Showing Fortifications along the Romney Marsh coast. The Nos. 21 to 27 refer to Martello Towers

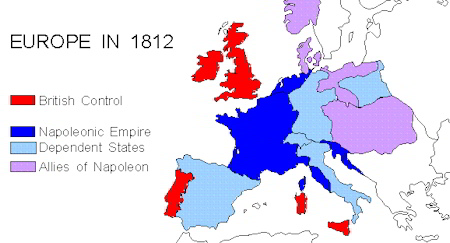

In the late 18th century and early 19th century, there were two periods of war with the French, generally known as the Napoleonic Wars.

1793 to 1802

It was in 1793 that the first war began, which is known as the Revolutionary War. In July 1789 the Bastille in Paris was stormed by the mob. In 1791 King Louis fled, only to be recaptured and guillotined in 1793. The French revolutionaries declared war on all the monarchies of Europe, and invaded the Austrian Netherlands, declaring war on Britain on 1st February 1793. So started twenty-two years of conflict.

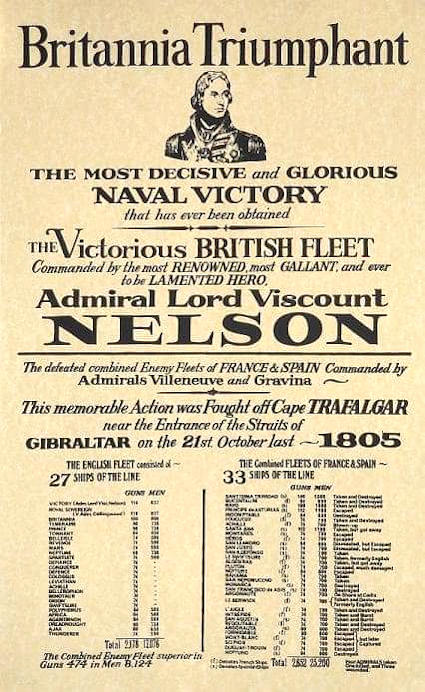

There was only a small British Army at the time and defence of the country mainly fell to the shoulders of the Navy. Even the Navy was not large; it grew from a peacetime size of 16,000 men to 100,000 by 1795. Nelson was at the time in charge of the Channel Fleet with fifteen ships of the line and fifty frigates. At one point in 1801 there was a huge French Army across the Channel ready to invade and all volunteers, were put on alert. The country became covered in large army camps full of both regular soldiers and the militias.

The fear of invasion was not entirely without foundation. In 1796 the French tried to land a force in Bantry Bay in Ireland and were only foiled by bad weather. Two years later they did succeed and 1,100 French troops landed in County Mayo where they were joined by some locals but not as many as they hoped and they re soon defeated.

In 1797 there was also a landing in Fishguard in Wales, which for some reason the French thought would also be an area where the locals would join them. Again they were disappointed and were soon defeated.

A peace treaty was signed in 1802 at Amiens, giving breathing space to both powers. This, however, was not the end of the wars and by 1803, war had been renewed.

1803 to 1815

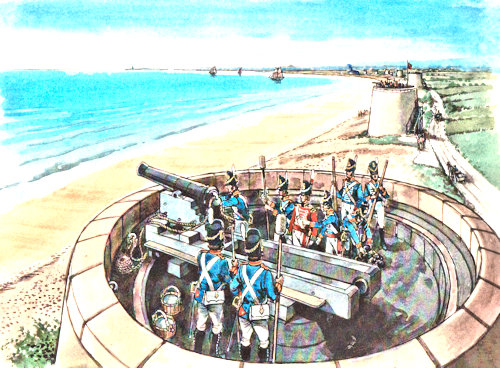

The fear of invasion after the outbreak of war again in 1803 was well-founded. For some time Napoleon apparently intended to attack England, concentrating a force of 130,000 men and thousands of barges and small boats along the French coast. This led to a new wave of defensive buildings and in 1804 sites were surveyed for several Martello Towers lining the coast, with larger redoubts interspersed between them. Although there had been some criticism of the building of these defences after Trafalgar, when invasion worries decreased, it should be remembered that the French Navy grew in size after its defeat by Nelson, so there was still a real danger of invasion. Some of these Napoleonic defences were later used in the battle against smugglers.

![]() Napoleon’s Threatened Invasion of England 1803-1804

Napoleon’s Threatened Invasion of England 1803-1804

Martello Towers along the Kent Coast in the UK

Napoleon, Nelson and the French Threat

For more than a decade in the late 18th and early 19th century, Britain faced the prospect of invasion by Napoleon. But how real was the threat and what defensive preparations did the British make?

War with France

When war broke out between Britain and Revolutionary France in the spring of 1793 there was no immediate threat of French invasion. Britain relied on the Royal Navy for defence and planned a series of sorties against the French forces in mainland Europe. But the picture started to change in 1796. French military successes and British military frustrations started to alter the balance of power and the British Government began to repair and reinforce coastal defences and to raise, train and equip a huge force of volunteers.

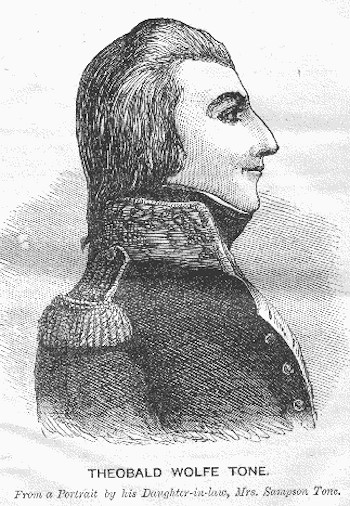

During 1796 the most successful and charismatic of France's revolutionary soldiers - General Hoche - started to hatch a grand and complex plan for the co-ordinated invasion of England, Wales and Ireland. Important to the French was the Irish patriot Theobald Wolfe Tone. A member of the Society of United Irishman Wolfe Tone was a Protestant who by the mid-1790s was convinced that change could come only through violent insurrection. In 1796 he was in France seeking aid and promoting the invasion of Ireland by a French army of liberation.

Wolfe Tone and Hoche met and their aspirations coincided. Wolfe Tone promised popular support if the French invaded and, in late December 1796, a French invasion fleet of around 50 ships carrying 15,000 veteran troops set sail from Brest for Bantry Bay in south-west Ireland. The plan was to land, ignite the country in rebellion against the Protestant English overlords, seize the port of Cork and be in Dublin within the fortnight. But nothing went right for the French - the weather was so violent that no troops could be put ashore - and by the first week of January 1797 the French invasion fleet, battered and dispersed, crept back to Brest.

Napoleon's Pro-invasion Policies

The failure of this and other invasion plans brought the British only a short-term reprieve. The Government continued to fear the enemy within and increased the power of sedition laws to break and stifle individuals and societies that appeared to be supporting pro-French Republican views. These fears seemed to be fully realised in April and May 1797 when elements of the Royal Navy - the first and major bulwark against invasion - mutinied at Spithead and the Nore. The mutiny - not primarily political in its nature - was dealt with and the British naval victory in October 1797 over a French-led and sponsored Dutch invasion fleet at Camperdown suggested that the Royal Navy was still in possession of its fighting spirit. But despite this British success the French still appeared to be closing in for the kill. General Hoche - the champion of invasion - died in mysterious circumstances in September 1797 but General Napoleon Bonaparte, whose prestige and power was rapidly on the rise following his victories in Italy, took up Hoche's anti-British and pro-invasion policies.

In late 1797 Bonaparte declared to the Directory Government that France

'must destroy the English monarchy, or expect itself to be destroyed by these intriguing and enterprising islanders... Let us concentrate all our efforts on the navy and annihilate England. That done, Europe is at our feet.'

When 1,100 French soldiers - led by General Jean Humbert - landed at Killala Bay on the 22nd August 1798 they came too late. The Irish were too demoralised or too terrified to join the French would-be liberators and Wolfe Tone - who could perhaps have raised more resistance in Ireland - was captured en route by the Royal Navy and subsequently committed suicide while waiting execution as a traitor. In early September Humbert surrendered his tiny army which - although the invasion proved futile - had given a good account of itself. But it was not Humbert's surrender that saved England from immediate invasion; that had been achieved before Humbert even set foot on the British Isles.

On the 1st August 1798 Admiral Nelson had destroyed a French fleet in Aboukir Bay - an action which not only marooned Bonaparte and his army in Egypt but also removed from France the ability to defend an invasion army as it crossed the English Channel. In March 1802 Britain appeared to have weathered the storm when, with the Treaty of Amiens, France - now a dictatorship with Bonaparte as the autocratic head-of-state - made peace with Great Britain. But both sides were intensely suspicious of each other, the terms of the treaty were not honoured and, in May 1803, Britain was once more at war with France, more powerful and a more sinister enemy than ever before.

Battle of Aboukir Bay

Hourly Threat

By the end of 1803, Bonaparte had amassed on the cliffs around Calais an Army of England 130,000 strong and a flotilla of 2,000 crafts to carry the host across the Channel. The presence of the army put huge pressure on the British Government to come to terms with Bonaparte who, in May 1804, had his position strengthened still further by getting the French senate to confer upon him the title of Emperor Napoleon I.

Napoleon realised that with invasion, as with most things, time was of the essence. If he could get his men ashore, getting them moving and to London, before the British could fully mobilise or deploy their forces then victory would be his. The British also realised that timing was all-important and knew that the job of its land-based defences - both coastal fortifications and volunteer regiments - was to delay and disrupt enemy forces until British regular forces could be gathered and a counter-attack launched. In the dark days of 1803 and 1804 - when a French invasion was expected on an almost hourly basis - Britain started to construct a vast network of coastal defences as well as relying on the skill and resilience of the Royal Navy. As Admiral Earl St Vincent said at the time: 'I do not say the French can't come, I only say they can't come by sea.'

The British reckoned the French would almost certainly choose the shortest invasion route and that they would aim to land at, or near, a port which, if captured, could be used for the rapid reinforcement and re-supply of its army. This pointed to three prime invasion targets: Dover and the beaches around it, Chatham and the River Medway (which the Dutch have successfully raided in 1667) and the flat, wide beaches of the Romney Marsh adjoining the small port at Rye. So Prime Minister William Pitt, a firm believer in the benefits of fixed fortifications, followed the advice of a number of military engineers, notably General Twiss, and approved plans to strengthen the defences of these prime targets.

Land Attack

The lines defending Chatham from land attack were strengthened by additions to Fort Amherst and by the construction of Fort Clarence. The greatest weakness of Dover was a vulnerability to land attack. The ancient castle - despite being greatly strengthened during the 1790s - was also vulnerable to attack from land, especially from the neighbouring Western Heights from which modern artillery could rapidly reduce the castle to ruins.

The answer hit upon by the military was to transform the Western Heights from the weak link in Dover's defence into its greatest strength. From 1804 until 1814 was turned into one of the great artillery fortresses of Europe. It housed batteries firing out to sea and inland, and barracks for a large garrison of troops that was given rapid access to the sea by means of the spectacular Great Shaft, a 140 foot deep cylinder containing three staircase designed to allow troops to move to and from the Western Heights and the harbour with maximum speed. The Western Heights was also provided with an impressive strong point - a place of great defensive and offensive power - called the Drop Redoubt. This fortress with its massive, brick-clad earth walls, deep ditch, well sited gun embrasures and vastly strong casemates and magazine remains one of the wonders of British post-medieval military design.

Portrait of William Pitt

by John Hoppner c1804

The defence of the Romney Marches was a trickier problem. Flooding was one possibility but this would have destroyed many homes and much productive land. In late 1804 a Royal Engineer colonel John Brown came up with a better idea: dig a 62-foot wide canal along the north edge of the march; keep its water level high with the use of sluices; and build a military road and rampart along its north bank so that it would function as a defended moat in case of French attack. The idea was approved immediately by Prime Minister William Pitt and the Royal Military Canal was completed by 1809. Its construction was a colossally expensive exercise - £234,310 - and was subsequently much mocked as an act of absurd military folly. William Cobbett's reaction in 1823, in his Rural Rides, was typical; 'Here is a canal ... made for the length of thirty miles ... to keep out the French: for those armies that had so often crossed the Rhine and the Danube were to be kept back by a canal.' Cobbett had a point but he missed the main one: the canal was only a part of a co-ordinated system of defence intended to wrong-foot the French invader, not to stop him.

Martello Towers

A similar purpose lies behind another of Britain's great, and much misunderstood, Napoleonic defences - the chain of 103 Martello Towers stretching from Seaford in the west to Aldeburgh on the East Anglian coast built between Spring 1805 and 1812. These squat, ovoid-shaped brick-built towers are immensely strong and were modelled on a gun tower at Martella, Corsica that had caused the Royal Navy much trouble in 1794.

Martello Towers were the idea of Captain William Ford of the Royal Engineers and they were sited roughly 600 yards apart and each mounted a long-range 24 pounder cannon. The aim was to cover the most likely landing beaches and to confuse any French landing while British reserves and Royal Navy ships were rushed to the area.

These towers were never tested which is a great tribute. The best defence is that which deters attack and certainly the French regarded these little 'bulldogs' as a formidable barrier. With hindsight it appears that all these defences were, essentially, pointless since Nelson's victory at Trafalgar in October 1805 - at the very moment the construction of the Martello Tower system was getting underway - made a French invasion of Britain a virtual impossibility.

Martello Tower No.24 on the UK Kent Coast

But in late 1805 the picture was not quite so clear. After the destruction of his fleet at Trafalgar Napoleon went on to win, in December 1805, the vastly important victory at Austerlitz that confirmed the French as the military and political masters of Europe. A French fleet could be reconstructed and, as far as the British could see, it was just a matter of time before the French were again in a position to invade. It was not until 1812 when Napoleon and his allies were smashed in Russia that the invasion of Britain was clearly beyond the French - and in this year the construction of the chain of Martello towers ceased.

Victory at Waterloo

The victory at Waterloo in 1815 left Britain the dominant power in Europe with the Royal Navy the strongest fleet in the world - despite suffering a series of significant but small-scale reverses during the War of 1812 with the fledgeling United States Navy. For 40 years threats of invasion were forgotten but then, in the late 1850s, emerged in a sudden and most dramatic manner. France - revived as an empire with immense territorial ambitions under Napoleon III - was once again the enemy and in the late 1850s Britain led by its Prime Minister Lord Palmerston undertook to spend vast sums on defence.

In 1859 a Royal Commission recommended the protection of Britain's main dockyards on both seaside and landward approaches with massive new forts being constructed at Portsmouth, Saltash, Plymouth, Milford Haven, Sheerness and Chatham. The total cost of these works - mostly completed during the 1860s - was a staggering $11.6 million, equal to around £520 million in modern money.

The speedy defeat of France by Prussia in 1870 and the ridiculous light it shed on the military worth of Britain's new and expensive generation of fortifications did not end the British fear of invasion. On the contrary, it merely identified a new enemy. Initially, the British had been gratified by the discomfiture of their traditional enemy but by the end of 1870 Prussian brutality, its cold-blooded military efficiency and its territorial ambitions had made it the next potential invader.

Source; Article by Dan Cruickshank for the BBC website

http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/british/empire_seapower/french_threat_01.shtml

Napoleon Bonaparte’s Plan for Invasion

Bonaparte's intentions in 1805 can be reconstructed partly from what he wrote at the time and partly from what he said later. Any plan he made had to take account of certain very particular points:

First, he must land in an area rich and productive enough to feed his army.

Second, this area must also contain a port where he could land such heavy equipment as guns and ammunition waggons, for both his field and his siege artillery, his engineers' stores and his hospital supplies.

Third, his own navy must hold the local command of the sea for long enough to protect the army's crossing.

Fourth, this last point made the time factor vital.

The deadliest risk run by an invader with only a temporary command of the Straits of Dover was having a reinforced British fleet arrive in strength, before his crossing was finished, to defeat his own navy and sink or capture his landing craft.

The longer the time he spent at sea, the greater this risk became, and a long voyage was therefore out of the question. Instead, he must land on some part of his enemy's coast which could be reached in a ten or twelve-hour voyage from Boulogne; and his need of a short voyage was made the more urgent by the fact that there was no way in which he could cut to less than three days the time he needed for embarking his troops and getting them to sea.

Bonaparte certainly did a vast amount of work to improve his invasion harbours. But the forces in Britain in 1803 were so much stronger than they had been in the earlier invasion crises of 1759 and 1779 that he would have had to land far more men in the island than Louis XV or Louis XVI would have needed, and the amount of shipping required to carry them was so large as to require six tides to get out of the invasion ports.

Source: ‘Britain at Bay’ by Richard Glover

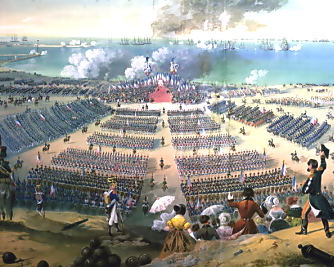

Inspection of troops at Boulogne, 15 August 1804

Plans to Resist Invasion by Napoleon

Meeting in New Hall Dymchurch September 1804

In the summer of 1804, British defence plans were developing and under critical review during this time. In a 'Memorandum as to the System of Defence', enclosed in a letter to Prime Minister Pitt in July 1804, the writer advocates the use of fireships (an interesting reversion to English tactics against the Armada in 1588) against the flotillas in Boulogne, Ostend and Le Havre. Significantly, he is not convinced that the navy can prevent a French crossing unless the blockade is made very close and the enemy are attacked as they come out. He criticises the stationing of so many men — regulars, militia and volunteers — in the north and advises that 16,000 troops march into the Southern District forthwith as the area is deficient in numbers 'thought necessary for its defence' by as many as 19,000 men.

From accounts taken from prisoners, the writer has been able to establish the extent and detail of the French invasion preparations. A regular system of embarkation had been laid down and of course, every general officer is furnished with general plans and maps of England and the general lines of march and operation'. The problem for the British Government, then, was not when would Napoleon come but where would he land and what would be done once he had secured a foothold.

Pitt and his military advisors could but look at the most vulnerable stretches of the coast and plan accordingly. One such stretch was that low-lying area of Kent called Romney Marsh. It was felt that should the enemy appear in force here then the only way to stop him would be to flood the whole area.

Accordingly, early in September 1804 Pitt, General Sir John Moore and Brigadier General Twiss met the Lords, Bailiff and Jurats of Romney Marsh* at New Hall, Dymchurch, to consider how best to inundate the Marsh if the worst should happen. Their decision was reported in the Kentish Gazette — the meeting agreed that, on the appearance of the enemy off the coast, the sluices should be opened to admit the sea so as to flood the dykes. This, it was said, might be done in one tide; in case of invasion, a further tide would flood the whole Level.

It was in part to facilitate this scheme that the Government took up the idea of building the chain of coastal fortlets called Martellos. A few of these were specifically sited to guard the sluices, although the plan, in general, was for strong points along the most vulnerable stretches of the coast.

In the late summer of 1804, Twiss conducted a survey from Dover to Beachy Head to determine upon the siting of the Martello Towers and the improvement of fortifications in general!' And so the year drew to a close. Napoleon had a vast force at his disposal with which to strike a decisive blow if he could but cross the Channel. Honed to a pitch of perfection, they could now embark 250,000 men in a mere ten minutes. The following year was to see the Emperor attempt to bring his plans to fruition by clearing away the first and greatest obstacle: the Royal Navy. In 1805, for the third year running, Britain once more faced the prospect of invasion.

The building of the Martello Towers commenced in spring 1805, but the guns for them were not landed until September and it was 1808 before the south coast towers were all completed. Work continued upon the Western Heights at Dover and guns were placed there to command the Folkestone Road. Napoleon arrived at his headquarters on 3 August, and on 6th summoned the Imperial Guard. Rumours of invasion now reached their height.

*The corporate body, under Royal Charter, 1252, responsible for land drainage and sea defence, empowered to levy local rates for this purpose.

Sources: ‘Kent and the Napoleonic Wars’ by Peter Bloomfield

General William Twiss

Napoleon Bonaparte was a military general who became the first emperor of France. His drive for military expansion changed the world. Napoleon Bonaparte was born in 1769 in France. He revolutionized military organization and training, sponsored Napoleonic Code, reorganized education and established the long-lived Concordat with the papacy. He died in 1821 in St. Helena.

Synopsis

Military general and first emperor of France, Napoleon Bonaparte was born on August 15, 1769, in Ajaccio, Corsica, France. One of the most celebrated leaders in the history of the West, he revolutionized military organization and training, sponsored Napoleonic Code, reorganized education and established the long-lived Concordat with the papacy. He died on May 5, 1821, on the island of St. Helena in the South Atlantic Ocean.

Early Years

Considered one of the world's greatest military leaders, Napoleon Bonaparte was born on August 15, 1769, in Ajaccio, Corsica, France. He was the fourth, and second surviving, child of Carlo Bonaparte, a lawyer, and his wife, Letizia Ramolino. By the time around Napoleon's birth, Corsica's occupation by the French had drawn considerable local resistance. Carlo Bonaparte had at first supported the nationalists siding with their leader, Pasquale Paoli. But after Paoli was forced to flee the island, Carlo switched his allegiance to the French. After doing so he was appointed assessor of the judicial district of Ajaccio in 1771, a plush job that eventually enabled him to enrol his two sons, Joseph and Napoleon, in France's College d'Autun.

Eventually, Napoleon ended up at the military college of Brienne, where he studied for five years, before moving on to the military academy in Paris. In 1785, while Napoleon was at the academy, his father died of stomach cancer. This propelled Napoleon to take the reins as the head of the family. Graduating early from the military academy, Napoleon, now a second lieutenant of artillery, returned to Corsica in 1786.

Back home Napoleon got behind the Corsican resistance to the French occupation, siding with his father's former ally, Pasquale Paoli. But the two soon had a falling-out, and when a civil war in Corsica began in April 1793, Napoleon, now an enemy of Paoli, and his family relocated to France, where they assumed the French version of their name: Bonaparte.

Rise to Power

For Napoleon, the return to France meant a return to service with the French military. Upon rejoining his regiment at Nice in June 1793, the young leader quickly showed his support for the Jacobins, a far-left political movement and the most well-known and popular political club from the French Revolution.

It had certainly been a tumultuous few years for France and its citizens. The country was declared a republic in 1792, three years after the Revolution had begun, and the following year King Louis XVI was executed. Ultimately, these acts led to the rise of Maximilian de Robespierre and what became, essentially, the dictatorship of the Committee of Public Safety. The years of 1793 and 1794 came to be known as the Reign of Terror, in which many as 40,000 people were killed. Eventually the Jacobins fell from power and Robespierre was executed. In 1795 the Directory took control of the country, a power it would it assume until 1799.

Napoleon Bonaparte

All of this turmoil created opportunities for ambitious military leaders like Napoleon. After falling out of favour with Robespierre, he came into the good graces of the Directory in 1795 after he saved the government from counter-revolutionary forces. For his efforts, Napoleon was soon named commander of the Army of the Interior. In addition he was a trusted advisor to the Directory on military matters.In 1796, Napoleon took the helm of the Army of Italy, a post he'd been coveting. The army, just 30,000 strong, disgruntled and underfed, was soon turned around by the young military commander. Under his direction the rebuilt army won numerous crucial victories against the Austrians, greatly expanded the French empire and helped make Napoleon the military's brightest star. His national profile was enhanced by his marriage to Joséphine de Beauharnais, widow of General Alexandre de Beauharnais (guillotined during the Reign of Terror) and the mother of two children. The two were married in a civil ceremony on March 9, 1796.

After squashing an internal threat by the royalists, who wished to return France to a monarchy, Napoleon was on the move again, this time to the Middle East to undermine Great Britain's empire by occupying Egypt and disrupting English trade routes to India.

But his military campaign proved disastrous. On August 1, 1798, Admiral Horatio Nelson's fleet decimated his forces in the Battle of the Nile. Napoleon's image was greatly harmed by the loss, and in a show of newfound confidence against the commander, Britain, Austria, Russia and Turkey formed a new coalition against France. In the spring of 1799, French armies were defeated in Italy, forcing France to give up much of the peninsula.

Inside France itself, unrest continued to ensue, and in June of 1799, a coup resulted in the Jacobins taking control of the Directory. In October, Napoleon returned to France. Working with one of the new directors, Emmanuel Sieyes, he hatched plans for a second coup that would place the two men, and another, Pierre-Roger Ducos, atop a new government, called the Consulate.

First Consul

Napoleon's great political skills soon led to a new constitution that created the position of First Consul, which amounted to nothing less than a dictatorship. Under the new guidelines, the first consul was permitted to appoint ministers, generals, civil servants, magistrates and even members of the legislative assemblies. Napoleon would, of course, be the one who would fulfil the first consul's duties, and in February 1800 the new constitution was easily accepted.

Under his direction Napoleon turned his reforms to other areas of the country, including its economy, legal system and education, and even the Church, as he reinstated Roman Catholicism as the state religion. He also instituted the Napoleonic Code, which forbade privileges based on birth, allowed freedom of religion and stated that government jobs must be given to the most qualified. Internationally, he negotiated a European peace. Napoleon's reforms proved popular. In 1802 he was elected consul for life, and two years later he was proclaimed emperor of France.

More War

Napoleon's negotiated peace with Europe lasted just three years. In 1803 France again returned to war with Britain, and then with Russia and Austria. The British registered an important naval victory against Napoleon in 1805 at Trafalgar, which led Napoleon to scrap his plans to invade England. Instead, he set his sights on Austria and Russia and beat back both militaries in Austerlitz. Other victories soon followed, allowing Napoleon to greatly expand the French empire, paving the way for loyalists to his government to be installed in Holland, Italy, Naples, Sweden, Spain and Westphalia..

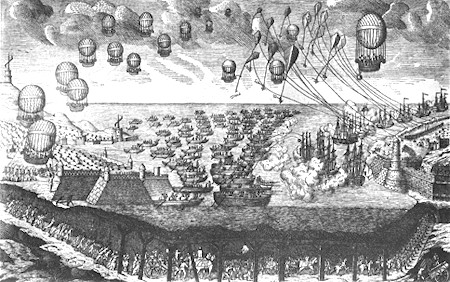

A French vision of the projected invasion, showing Napoleon's troops

crossing the Straits of Dover by barge, balloon and what must be the first Channel tunnel. In a further flight of fantasy, English soldiers, suspended in

the sky from kites, are shown firing their muskets at the invading balloons

(HULTON PICTURE LIBRARY)

Changes were also afoot in Napoleon's personal life. In 1810 he arranged for the annulment of his marriage to Joséphine, who was unable to give him a son, so that he could marry Marie-Louise, the 18-year-old daughter of the emperor of Austria. The couple had a son, Napoleon II (a.k.a. the King of Rome) on March 20, 1811.

Napoleon's military success, however, soon gave way to broader defeats, beginning in 1810, when France suffered a string of losses that tapped the country's military budget. In 1812 France was devastated when its invasion of Russia turned out to be a colossal failure in which scores of soldiers in Napoleon's Grand Army were killed or badly wounded. Out of an original fighting force of some 600,000 men, just 10,000 soldiers were still fit for battle.

News of the defeat reinvigorated Napoleon's enemies, both inside and outside of France. A failed coup was attempted while Napoleon led his charge against Russia, while the British began to advance through French territories. With international pressure mounting and his government lacking the resources to fight back against his enemies, Napoleon surrendered to allied forces on March 30, 1814. He went into exile on the island of Elba.

Return to Power

Napoleon's exile did not last long. He watched as France stumbled forward without him. In March 1815 he escaped the island and quickly made his way to Paris, where he triumphantly returned to power. But the enthusiasm that greeted Napoleon when he resumed control of the government soon gave way to old frustrations and fears about his leadership. Napoleon immediately led his country back into battle. He led troops into Belgium and defeated the Prussians on June 16, 1815. But then, two days later, at Waterloo, he was defeated in a raging battle against British, who were reinforced by Prussian fighters. Napoleon once again suffered a humiliating loss.

Later Years

On June 22, 1815, he abdicated his powers. In an effort to prolong his dynasty, Napoleon pushed to have his young son, Napoleon II, named emperor, but the coalition rejected the offer. Additionally, fearing a repeat of his earlier return from exile, the British government sent him to the remote island of St. Helena in the southern Atlantic.

For the most part, Napoleon was free to do as he pleased at his new home. He had leisurely mornings, wrote often and read a lot. But the routine of life soon got to him, and he often shut himself indoors. His health began to deteriorate, and by 1817 he showed the early signs of a stomach ulcer or possibly cancer. By early 1821 he was bedridden and growing weaker by the day.

Napoleon’s Return from Elba by Charles de Steuben, 1818

In April of that year, he dictated his last will: "I wish my ashes to rest on the banks of the Seine, in the midst of those French people which I have loved so much. I die before my time, killed by the English oligarchy and its hired assassins."

Napoleon died on May 5, 1821.

Source http://www.biography.com/people/napoleon-9420291 and where you can listen to an audio about Napoleon

The Peace of Amiens, signed in March 1802, had ended nine years of war with Revolutionary France, but Napoleon's territorial ambitions in Europe and elsewhere were to ensure that peace was short-lived. On 18 May 1803, faced with clear evidence of France's expansionist aims and unwilling to tolerate Napoleon's control of Holland, England declared war.

England Heritage Guide to Martello Tower No.24

The Invasion Coast 1803

Dymchurch Martello Tower - no 24 in a chain of 74 built along the Channel coasts of Kent and East Sussex between 1805 and 1812 - was constructed to meet a threat of invasion as serious as the later one which faced England after the fall of France in the summer of 1940.

The Peace of Amiens, signed in March 1802, had ended nine years of war with Revolutionary France, but Napoleon's territorial ambitions in Europe and elsewhere were to ensure that peace was short-lived. On 18 May 1803, faced with clear evidence of France's expansionist aims and unwilling to tolerate Napoleon's control of Holland, England declared war.

For the first two years of the war, Napoleon's main aim was the invasion and subjugation of Great Britain. To that end, three army corps, all seasoned veterans of earlier campaigns, were ordered to the Pas de Calais and encamped on the coast between Calais and Étaples. To transport this Grand Army to England, Napoleon ordered the construction of an armada of flat-bottomed barges, to be supplemented by fishing boats and other small craft. Ambleteuse, Wimereux, Boulogne and Étaples were the principal construction and assembly ports for this vast fleet, but Calais, Dunkirk and Ostend played important supporting roles. Two years after the renewal of war, Napoleon had invasion shipping for almost 168,000 troops and equipment. `Let us be masters of the Straits for six hours' he had said in July 1804, adding modestly `and we shall be masters of the world'.

On land, Great Britain could not hope to match Napoleon's experienced professional troops. In 1803 the regular army stationed in England numbered only some 60,000 men; to this were added 50,000 militia and in 1804 about another 30,000 men forming the Army of Reserve. In addition, some 300,000 men flocked on the outbreak of the war to form the Volunteers, a part-time force of infantry and cavalry. The Volunteers were ill-equipped and lacked training and experience, but such deficiencies were counter-balanced to a certain extent by patriotic enthusiasm. Indeed, the very existence of the Volunteers is witness both to the unity of the country in 1803 and to a widespread feeling that a French invasion was all too probable.

The deployment of these troops called for careful judgement by the Commander-in-Chief, the Duke of York. London and the main naval arsenals - Chatham, Portsmouth and Plymouth - were obvious centres for defence, the naval towns fortunately comparatively well protected by permanent fortifications. However, it was realised that the best hope of stopping a French invasion was either to annihilate the invasion fleet at sea or to defeat the army at its beachhead, preferably while it was still struggling ashore, but certainly, before it could land its equipment and secure a port for artillery, reinforcements and supplies.

Map of English Channel

Napoleon's obvious invasion route was the shortest sea crossing. The transports being built and assembled were nor suitable for a voyage of more than about 24 hours, while the shorter the passage the less the troops were likely to be debilitated by sea-sickness. There was moreover, one over-riding and decisive factor favouring a quick crossing. French armies might be supreme in Europe but at sea, it was the Royal Navy that exercised power. Almost alone, the Admiralty remained largely unperturbed by fears of invasion: in the House of Lords, St Vincent, First Lord of the Admiralty, sought to calm his fellow peers. `I do not say, my Lords,' he observed, `that the French will not come. I only say that they will not come by sea.'

St Vincent had reasonable cause for confidence. At the outbreak of war, the Royal Navy had around 640 fighting ships, including 177 of the larger ships-of-the-line; by January 1805, the total had risen to around 820. The Channel fleet, under Admiral Cornwallis, patrolled the western approaches and kept guard on French warships in Brest and Rochefort, while Admiral Lord Keith exercised a similar command east from Selsey Bill round into the grey waters of the North Sea. The Grand Army overlooking the Channel from its cliff-tops outside Boulogne, the shipwrights hard at work on the invasion flotillas from Ostend to Etaples and the French Army staff were all well aware of the weather-beaten cruising squadrons patrolling off-shore and of the power they represented. This disciplined use of maritime strength, exercised in all weathers, may have given much repair work to the English dockyards, but it ensured that the Royal Navy's training and seamanship were unrivalled.

Although British army planners could not be certain of Napoleon's exact choice of invasion beach, they could make reasonable deductions, knowing the geographic and estimating the logistic limitations within which the French general staff would have to work. An invasion fleet needed to land on shallow beaches adjacent to low ground; once ashore, the troops would have to capture a port to bring in heavy supplies such as an artillery train and would require access to rich countryside capable of feeding an army. Within the necessary short sailing-time from France, the low-lying beaches between Sandgate and Eastbourne seemed the most probable targets for an invasion, followed by a French encirclement of Dover and the capture of its vital harbour. Further to the north, the coasts of Essex and Suffolk, although suitable for an army intent on London, were felt to be less vulnerable if only because of their greater distance from France.

But, despite the good British seamanship, there was always the possibility of a powerful French fleet escaping from Brest unnoticed, sailing up the Channel and securing the Straits just long enough to allow the French army to cross to England. Such an eventuality was outlined in a report from Lord Keith to the Duke of York, Commander-in-Chief of the army, in October 1803. Indeed, Lord Keith's assessment bore considerable similarities to Napoleon's later orders to Admiral Villeneuve in the Spring of 1805. By then, Napoleon had probably repented of his boast that France needed to secure the Straits for only six hours, for an army the size of his invasion force would have needed a minimum of three days just to embark and put to sea. None the less this risk of the French securing temporary mastery of the Straights led to increasing demands in England for better invasion defences.

An 1803 cartoon depicting John Bull stopping the invader Napoleon with

a pitchfork, whilst his wife empties her chamber-pot over him.

In the background, French troops flee in disorder

(HULTON PICTURE LIBRARY)

Defending the South Coast

The British government, well aware of the strategic importance of this region of Kent and East Sussex, had been strengthening its defences since 1793. At Dover, among other works the medieval castle was modernised and given additional gun batteries and a vast fortress was started on Western Heights opposite it. These fortifications were not just to protect harbour and town; they could accommodate sufficient extra troops to oppose an invasion in the vicinity.

The area of Romney Marsh, too, had received attention from military engineers. Schemes to flood it in the event of invasion were found to be impracticable, but by 1804 fifteen fortifications existed between Folkestone and Lydd, with those at Dungeness giving protection to ships anchoring on either side of Dungeness Point. Further west, the low-lying area of the Pevensey Levels was similarly protected by some 19 gun-batteries while, inland, river-crossings at places such as Newenden, Bodiam and Robertsbridge were guarded by small batteries. Most of these defences, though, were simple fieldworks. They were built of earth with timber or brick revetments and timber gun platforms and, while cheap to construct, they were in no sense permanent fortifications. They varied widely in size and power: Shorncliffe, the most substantial battery, mounted ten 24-pounder guns; in contrast, a sluice at Dymchurch was protected by a single 18-pounder weapon. How much of an obstacle they would have been against an assault by Napoleon's experienced troops was debatable.

.jpg)