Smuggling

![]() Introduction

Introduction

![]() Coast Blockade Service

Coast Blockade Service

![]() Churches and Smuggling

Churches and Smuggling

![]() Local Smuggling

Local Smuggling

![]() The Smuggling Gangs

The Smuggling Gangs

![]() Dr Syn

Dr Syn

![]() Pictures and Poems

Pictures and Poems

Five and twenty ponies,

Trotting through the dark -

Brandy for the Parson, 'Baccy for the Clerk.

Them that asks no questions isn't told a lie -

Watch the wall my darling while the Gentlemen go by!

Part of the poem The Smugglers Song

by Rudyard Kipling

Picture courtesy of Terry Anthony ►

See larger picture

Romney Marsh was said to be the birthplace of smuggling in southern England. The fertile land reclaimed from the sea made fine grazing for hundreds of thousands of sheep, and the export of the wool from their backs was for centuries both highly taxed and badly policed — almost an open invitation to smuggle. Read about the Romney Sheep

Illegal wool exports from the Marsh probably started the very first day that restrictions were imposed: in 1275 the government introduced a tax of £3 a bag on wool leaving England. This was doubled in 1298, and successive administrations tinkered with the laws and duties according to their need for funds. It was made illegal to export wool from other than designated ports in an attempt to protect our own clothing trade.

Wool smuggling from Romney Marsh fluctuated in response to the laws, and to market forces; high demand at home meant there was less incentive to smuggle. In the 15th century, though, the reverse happened, and as wool prices fell, the producers found it harder to make a living from the home market. The expansion of smuggling was inevitable.

'The Ship'

It was in the 17th century that the problem assumed epidemic proportions, and attention was focused firmly on Romney Marsh as the centre for the trade. In 1698, the Act to Prevent the Exportation of Wool was passed which prevented the export of wool. With the death penalty introduced for smuggling wool, the legislators of the day probably saw this as a major deterrent, but if anything, it simply made the owlers of Romney Marsh more desperate still. If you're to hang for smuggling wool, why hesitate to shoot your pursuer?

In the 18th and early 19th centuries smuggling continued to be rife in on the Romney Marsh, both in fact and in the fictional stories of Dr Syn. Spirits, silk, lace, tea, tobacco and such like were smuggled in while tin, graphite and particularly wool, were smuggled out.

Smuggling on the Marsh was at its height during the period from 1700 to 1840.

It was the vast open areas of the Romney Marsh, and the quietness and the closeness of the French coast which can be seen on a clear day which made the area perfect for smuggling.

It was soon though to be a very easy task to carry out illicit trading, as there would be very few Revenue men around. Most smugglers fished for a living. They knew the Channel very well and would meet the French half way and exchange goods in the darkness to their advantage.

Smuggling started way back in the 14th century. Early smugglers were known as Owlers as they only worked at night using the hoot of the owl as a signal. Their task was not so much smuggling in, as smuggling out. Their valuable cargo was wool, being given the name Canterbury wool.

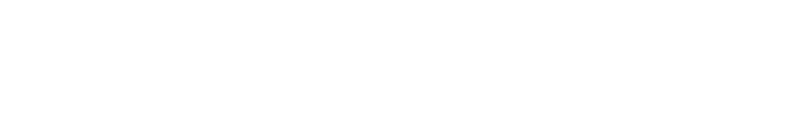

Smugglers Cartoon

The Romney Marsh was a vast sheep rearing area and a short distance across the Channel. Wool was in demand both here and abroad, finding its way to Holland and Belgium. Prices were very high on the Continent.

In the beginning it started small with family and friends. Activities known to the King’s men were often ignored after a small sum of payment. Early smugglers were even looked upon with some affection. By the 18th century things had changed. The Revenue men were very short staffed in trying to prevent smuggling and very often when they did make an arrest, juries refused to convict, thus making matters worse.

From the small and harmless beginnings, it grew into a very ruthless and serious threat to law and order. In the 18th century, having spread throughout Kent and Sussex, this part of Kent was dominated by some of the most wicked and ruthless smugglers in the area. They would stop at nothing to achieve their aims. They would even kill family or friends as a deterrent if they thought they were a threat.

'Smugglers'

The harmless fishermen were soon to become thugs, highwaymen and desperadoes. They feared nobody and ran their schemes without interference due to their threat of reprisals. By the 1780's an estimated six thousand pounds were lost in revenue.

The Coast Blockade Service was created in 1816 following the country’s huge loss of revenue due to what was then considered by some to be a lack of success by the Customs and Revenue Services in coping with the smuggling problem.

At the end of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815, Captain Joseph McCulloch proposed the creation of a unified service to guard the coast of Kent where he was at that time commander of a Royal Navy ship supporting the Revenue Service. He proposed that the shore patrols, the in-shore water patrol and the off-shore cruiser activity should all be united under a single command. So in 1816, the Coast Blockade Service was created under McCulloch’s command on the Kent coastline between North Foreland and Dungeness. This proved to be highly successful but not popular.

Smugglers landing on Romney Marsh

By 1820 there were 6708 officers and men, including 2375 men on 31 Royal Navy ships, operating at a total cost of just under £521,000. There was considerable scope for confusion and duplication because of the fragmented approach. In 1821 a committee examining the operation of the Customs recommended the combination of all services (except the Coast Blockade which would remain under the Admiralty) under the control of the Board of Customs.

The Coastguard Service came into operation in 1822. In 1831 the Coast Blockade was absorbed into this new service.

Coastguards served on ships and onshore. Men on shore were moved away from their home location for fear of collusion. Coastguard Stations were equipped with living quarters for married men as well as single quarters. Each station was commanded by a Chief Officer (normally a Royal Navy lieutenant). Beneath him were Chief Boatman, Commissioned Boatman, and Boatman ranks. The size of the station determined the number of each rank. By 1839 there were over 4553 Coastguards.

![]() Reference and more information

Reference and more information

Taken from an original watercolour painting by Anita Walden

Many of the mediaeval churches on the Marsh were involved with smuggling. The churches at Brookland, Ivychurch, Snargate and the isolated Fairfield all made good places for the smugglers to hide their contraband goods before their distribution. Obliging Sextons would open up convenient vaults and remove their contents in order to store brandy, tea, tobacco, silks, laces, fine gloves and many other goods. In one church, the font was used as a hide.

At Ivychurch, part of the flooring of the north aisle was removable to enable contraband to be hidden away in the vault beneath. In Dymchurch churchyard there are tombstones to Preventive men and Riding Officers, the law of the day. At Snave, there are two tombstones that are believed to be of smugglers.

At Snargate in the 18th and early 19th centuries, a section of the north aisle was sealed off by a partition and this was frequently used as a hiding place. Also in Snargate, there is a painted galleon opposite one of the doors which, it is said, told the smugglers that the church was a safe hiding place. At New Romney, the ruined church of Hope All Saints was a smugglers' meeting point.

The smugglers of the old days were a sad and sorry lot. Their crimes were despicable and horrific, yet they thought they were justified, as they were helping to support the community. They thought themselves higher in status than, say, the pirate or highwayman, who worked for their own gain whereas the smuggler pitted his wits and courage against the law. For them, smuggling was the people versus the law.

Picture of Smugglers

One of the most notorious smuggling gangs ruled throughout Dymchurch and the surrounding area. They were the Aldington gang or the Blues as they were also known. They rose to fame in the nineteenth century.

They worked the coastline from Deal down to Camber in East Sussex. The first leader of the gang in the early days was Cephus Quested. They were extremely successful until 11th February 1821, when on a run they came face to face with the blockade men.

Among the dead and wounded two prisoners were captured, Richard Wraight and Quested himself. Wraight was released with no evidence offered. Quested was found guilty to be hanged. After the battle the gang went its own way for a while.

Ransley was finally betrayed by two members of his own gang; a party of blockade men assisted by a Bow Street runner forced entry to his home and arrested him, and soon rounded up the rest of the gang. On January 12th 1827 they were brought to trial in Maidstone, accused of murder, smuggling and taking up arms. They were defended by their lawyer from Ashford. They pleaded guilty and were sentenced to hang, the death sentence being quashed after finding out the evidence being given incriminated people in high places, a case of saving skin. Ransley and his men were sent to Portsmouth and imprisoned on a hulk for three months, before being transported to Tasmania, never to return. Ransley worked hard on a prison farm, later being given his own land to work. His family later joined him, and they became quite wealthy and friends of the community.

Galleon Painted on the Wall of Snargate Church

Ransley died of yellow Jaundice aged 77, and so fell the curtain on one of the biggest gangs, ending an era. Smuggling still exists today but cargoes are far less lethal than in times past

The Owling trade brought about the very first smuggling gang, based in Mayfield in 1720. Rochester and Faversham prospered from the trade, both legal and illegal. Whitstable was also well known for its smugglers, a street called Island Wall being the centre of their attractions.

Many individual smugglers have earned a place in history. Samuel Jackson, or Slippery Sam as he became known, was born in 1730. The son of a smuggler, he lived in Petham, near Canterbury. Slippery Sam met his end at the age of thirty after being shot in a battle.

As free traders became more organised they fell into two classes, master men and labourers. The most notorious of these was the Hawkhurst gang. They terrorised and reigned along the cost for several years. One member, thought to be the leader, was Arthur Grey.

The gang operated the coast from Shoreham to the Romney Marsh. In a battle with militia men some members were caught, including Arthur Grey.

Smuggling on the Romney Marsh (ack.8)

They were all acquitted as no evidence was offered. Several of the gang were captured later and taken to trial in 1749. This time they were found guilty and sentenced to seven years transportation.

North Kent gangs worked the coast from Medway to Ramsgate, Reculver being their favourite landing spot. Another famous smuggler, born in St Peter’s in 1741, was Joss Snelling. He was successful and, as a result, few of his activities were recorded. In 1769 his gang was involved in a battle which became known as the battle of Botany Bay.

Eight were captured and injured. Snelling was captured by the Revenue men. On 10th August 1803 he pleaded not guilty, claiming he came across the contraband by chance. He was released and spent the rest of his life smuggling, along with his son George and grandson. He was even presented to the future Queen Victoria. He died a smuggler, aged 96.

Smuggling thrived in Deal throughout the 18th century. Gin, brandy and tobacco were still being seized as late as 1880. Deal ship builders developed a type of speed boat, the galley. It was long with a small sail. It made many crossings, which proved costly to the government. In 1784 William Pitt, Prime Minister, ordered the destruction of these boats. By 1785 more than 400 people were reported to be involved in smuggling within the Dover area. Smugglers were even used by Napoleon for carrying papers, letters and even their spies across the Channel.

'The Smuggler'

The Dr Syn is the smuggler hero of a series of novels by Russell Thorndike, which were set in and around Dymchurch. For more information please visit our Dr Syn page.

Greatstone resident Anthony Webb has written a number of poems about Romney Marsh, with a main theme of 18th smuggling on the Marsh. All the poems are illustrated, examples above, by various artists. You can read them on our Anthony Webb page.